As one whirls into Parkside Hall, a map of the Islamic World, circa 1200, extends from Northern Africa and Spain in the west, through the Middle East and onward to India and then southward as far as Mali and Sudan. Timelines document significant contributions by Muslim scholars to various fields, circa 8th to 18th centuries C.E.

The initial placards collectively function as an overarching framework for the Tech Museum‘s current exhibit Islamic Science Rediscovered: Celebrating a Golden Age of Science and Technology. From there, one ventures in to experience a wealth of information. Large clusters of placards divide the exhibit into numerous categories with titles like “Great Explorers, “Math, Art and Architecture,” “Water Raising Machines,” “House of Wisdom,” “Astronomy” and more.

First things first. There is nothing controversial about the exhibit whatsoever. It is not religious or political. Although nowhere near as big as the Leonardo show, Islamic Science does provide a smattering of reading material, a few interactive displays and a few videos. If you miss any sordid details, the Tech Museum’s wandering employee-scholars will fill you in.

The optics cluster explains how Islamic scholars laid the foundations for modern optics. The medicine cluster features perhaps the most intricate display of minute Islamic surgical tools anywhere. There are homemade bone saws, chisels, scalpels, a tongue depressor and a “tonsil guillotine.”

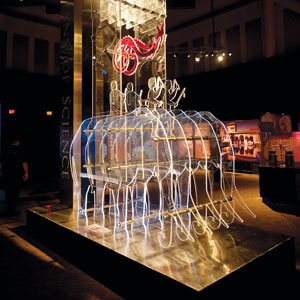

Another section titled “Fine Technology and Inventions,” highlights the machines and autonomous projects of al-Jazari, a polymath, scholar, inventor and overall engineering genius of the Muslim world in the Middle Ages. Before Da Vinci came up with his ideas for automata, al-Jazari designed programmable humanoid robots, plus a number of inventions, including a precursor to the modern-day automobile crankshaft. A huge replica of his elephant water clock stands in the middle of the exhibit, although it was broken upon my visit.

Over in the House of Wisdom cluster, one receives enlightening facts about Ibn Khaldun, the legendary historian considered by many to be one of the founding forefathers of modern-day economics and sociology. Khaldun’s philosophies have crept up in many circles over the centuries, especially his concepts of tribalism, nomadism, plus the rising and falling of cohesive societies.

Also portrayed in the House of Wisdom is al-Jahiz, the classic Arabic prose writer and author of the encyclopedic Book of Animals, the first tome to discuss animal communication, intelligence and social organization.

But unfortunately, with Parkside Hall as the venue, the exhibit does not always come across as a high-end museum experience. The carpets are worn, and some of the stands holding the placards are scuffed up.

Parkside Hall is basically the old convention center from the ‘70s—universally recognized as the building where everyone went for the vacuum cleaner demonstrations at Tapestry ‘n’ Talent—and for me it doesn’t come across as a museum space by any stretch.

Some utterly fantastic stories emerge from the show. One gains insight about individuals either long forgotten or relegated to footnotes or antiquarian interest, even though their ideas and inventions predated anything in the West by centuries. The “who knew” factor emerges from every section of the show.

Long before anyone else, Muslims used catgut to close surgical wounds and also discovered the pulmonary circulation system. Houses of Wisdom were precursors to modern libraries and universities. Over a thousand years ago, in front of a crowd on a hill near Cordoba, Spain, Abbas ibn Firnas—the world’s first aviator—climbed into the harness of his glider, launched himself into the air and flew across the Spanish countryside. Now that is inspiring.

Islamic Science Rediscovered

The Tech Museum, San Jose

Get More Info on Islamic Science Rediscovered at the Tech Museum

TECH UPDATE: Steve Jobs Day, Google is Audited

TECH UPDATE: Steve Jobs Day, Google is Audited  Live Feed: Occupy Earth

Live Feed: Occupy Earth