The glistening black moustache spirals downward and outward—riotous parentheses for the red-veined drinker’s nose protruding far beyond the shelter of a towering sombrero.

Pop-eyed, dilated, soul-patched and stylishly draped, the 4-foot figure, sculpted impossibly of vividly transparent blown glass, stands with shoulders flung back, belly thrust forward, hands angling up from the wrists, in a “Whaaa—hey, man, I didn’t do it’ gesture.

El Immortal by the de la Torre brothers welcomes visitors to Mexicanismo Through Artists’ Eyes, just opened at San Jose Museum of Art.

Spare but surprising, Mexicanismo brings together 13 Mexican and Mexican-American artists who draw on traditional and folk arts in meticulously crafted works whose often humorous and sometimes wrenching impact is achieved by tugging at the strings of cultural stereotypes.

El Immortal is a tattersall-checked Mexican dandy with dong-shaped bongs hanging from every seam. His leather huaraches tip atop a pedestal of glass that mimics a gleaming car rim embellished in gold and snakeskin. Busted—gorgeously. Artists Jamex and Einar de la Torre, born in Guadalajara, now ply their exquisite glass ironies internationally.

Nearby, Maximo Gonzalez has woven two 13-foot mats from strips of paper currency—the ends and edges sliced from print runs of different denominations, cast-offs from the Mexican mint. Gonzalez has long used currency in works that refer to the constant devaluation of the peso. Humble Oaxacan floor mats: Has the peso reached bottom yet?

Gabriel Kuri commissioned traditional weavers of Guadalajara to fashion tapestries in the technique used to create the luxuriant tapestries commissioned by Louis XV of France in the 15th century. Those Gobelin tapestries depicted mythological or historical tableaux glorifying the church or the monarchy. Kuri’s Guadalajara weavers painstakingly hand-knotted 7.5-foot-long creamy tapestries with spidery lines of type: cash register receipts from big-box stores. Glorifying?

In a Mexican craft tradition as old as the Olmec civilization, delicate clay flora and fauna embellish the “arbor de la vida,’ or tree of life. Margarita Cabrera repurposes these gentle glorias as ceramic homages to the tools of hard physical labor. Her slip-glazed hammer, shovel, saw and pick are covered in delicate flowers and birds, elevating these crude instruments into objects of reverence.

Nearby, a table is set for a party with colorful tablecloth and cushions painted with flowers in the Pano style that originated as a small industry for Mexican prisoners who thus embellished handkerchiefs.

Natalia Anciso lets loose with vivid florals whose luscious blooms and spiraling tendrils camouflage grim drawings of border incidents—forlorn captives cower under vivid poppies; gun-wielding vigilantes lord it over exhausted families. Underneath florid fantasies: heartbreak.

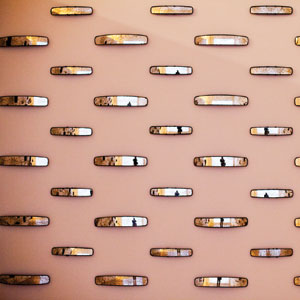

The most arresting and memorable work in Mexicanismo is the installation De Reojo by Betsabe- Romero. The Mexico City artist mounted more than 100 rear-view mirrors aimed at a wall acting as a screen for video shot from a moving car, documenting empty streets of Ciudad Juarez.

In this border town, more than 400 women on their way to work in isolated pre-dawn streets have been murdered in recent years and hundreds more kidnapped and raped. Three walls of mirrors reflect that lonely journey. On each, a floral design in black signifies the feminine: a pattern copied from the cloak of the Virgin of Guadalupe. “Like the gaze of infinite women who travel everyday/dangerous trajectories É like a glance tattooed with prayer É’ in a poem by the artist. It’s a visually rich and emotionally stunning installation.

Curator Kristen Evangelista began organizing Mexicanismo years ago, engaging with San Jose communities to create a sturdy springboard for the sometimes provocative ironies.

Mexicanismo Through Artists’ Eyes

Runs through Aug. 26

San Jose Museum of Art

Stage Review: Buffalo’ed

Stage Review: Buffalo’ed  Tofu Misozuke in Silicon Valley

Tofu Misozuke in Silicon Valley