Walter De Brouwer is not like most people. If he was, most people would be Belgian. Most people would also be described as someone “who thinks thoughts that may have never been thought before.’

That was the hyperbolic introduction De Brouwer received last weekend, but after listening to the wild-haired Belgian speak for 20 minutes, the billing didn’t seem so inflated. De Brouwer thinks thoughts that have been thought before, just never taken too serious outside of science fiction circles. The 54-year-old entrepreneur, publisher, scientist, futurist and tech pirate wants to put America’s for-profit health care system on life support, and he says the process is only a year away from beginning in earnest.

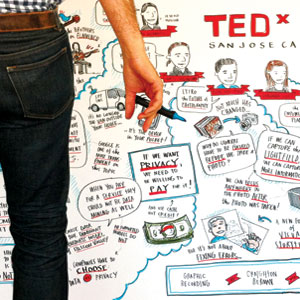

A featured guest at TEDx, the Technology, Entertainment and Design (TED) conference, held April 14 at the Bellarmine Preparatory campus in San Jose, De Brouwer was one of a number of speakers who take everyday concepts and then expand them to a radical scope. The events are independently produced around the world. San Jose’s TEDx included teenage scientists and CEOs; professors identifying revolutionary ways to combat human trafficking and environmental destruction; and an enemy of state-sponsored spying, amongst others.

De Brouwer took a different subject to task: incompetent doctors. In past interviews, the former tech-punk publisher and founder of Starlab—to understand the company’s abstract goals think lasers and light years—has dismissed physicians as “drug dealers.’

De Brouwer’s current corporate focus, Scanadu, which operates out of NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field in Mountain View, plans to release in the next year its tricorder, a Star Trek-inspired medical sensor device. The equipment passes data on to an electronic monitor the size of the first cell phone, using a corded wand waved over problem areas of the body. The idea is a contactless scan, which reads sensors placed inside the body, will report the malady—high temperature, skin rash, urinary tract infection, etc.—and its severity rather than keeping people tethered to hospital waiting room chairs.

“I think we will be the last generation that knows so little about their health,’ De Brouwer says.

If successful, Scanadu could revolutionize a health care system that rewards pharmaceutical companies and disinterested doctors, who De Brouwer depicts as fortunetellers and drug peddlers to the world’s hypochondriacs.

“You are the narrator,’ De Brouwer says. “The doctor doesn’t say anything. He just sits there. You are actually diagnosing yourself. That’s why they have a white coat, otherwise we would confuse them with normal people.’

De Brouwer’s complex relationship with health care and diagnoses comes from learning far more about the industry than he ever wanted to. In 2006, his son suffered a traumatic brain injury and went into a comatose state known as Glasgow 3.

“Many of you probably don’t know what this means,’ De Brouwer says to the TEDx audience, “and in this case ignorance is bliss.

“Glasglow 3 is electrical death,’ he tells me later in the day. “So it means life has gone but the body still has some electricity. But the content will never come back.’

Spending almost every hour for the next three months in an assortment of trauma wards, De Brouwer gained a detailed knowledge of the inefficiencies of the health care system, and it led him to wonder what it must be like for others unable to get an accurate diagnosis.

Scanadu plans to minimize breakdowns by empowering everyday people on a global scale. “We are six months to a year away,’ De Brouwer says, noting that Scanadu’s internal sensor still needs to be fully designed as well as a database of tagged ailments and symptoms. “Of course, the more people who use it the better it works. Like money.’

But De Brouwer’s motivation, like many at TEDx, didn’t start with dollars. “Anyone can build a better mousetrap to get some more money,’ he says, “but when you’re personally involved and committed, you know, you want to go to extremes. I think people like pirates who want to disrupt things.’

Enter Christopher Soghoian, TEDx’s scruffy watchdog of corporate greed and government espionage.

Data Discord

A person walks into a grocery store and finds two prices for milk. One costs $5 if the customer doesn’t want to sign up for a loyalty card, and the other costs $3 a gallon with a scan of the card. A scan allows the store store to build a profile around a person and target them with offers. And yet, as Christopher Soghoian explains, when it comes to email and social media profiles, we have no opt-out ability. Therein lies the shadow war that is taking place on consumers’ privacy.

“There’s no Facebook Pro or Facebook Private, where you can pay $5 for it and Facebook will then treat you like a customer instead of a resource to be mined,’ says Soghoian, dressed casually in jeans and a black National Security Agency t-shirt. “The services are offered in one model and they’re take it or leave it. The problem is it’s fine if it’s a search engine, where there are other services to be used. But particularly the social services, there’s a coercive aspect to them. If you don’t use a social network that your friends are using, you’re left out of the conversation. … You’re missing a vital part of the conversation amongst your peers, so it means it’s really difficult for people to say ‘no.’‘

Soghoian, who lives in Washington D.C., doesn’t seem to be one of these people. “I’m far more paranoid than the average person, but I don’t feel I’m unreasonably paranoid,’ he says with a grin. “Rather than trying to protect my own privacy, I try to spend my time getting companies to better protect their users. If I can get one company to change one thing, then it impacts millions of consumers, including me.’

An example of Soghoian’s work includes leaking an audio recording in 2009 that featured a Sprint Nextel executive revealing that the company handed millions of subscribers’ GPS information over to law enforcement.

“In many ways it would be illegal for the government to directly collect it—for the government to directly attach a GPS to our vehicles,’ Soghoian says. “It would be illegal for them to do that without a warrant. But they can force Verizon, or Sprint or T-Mobile to hand over that data. They can force Google to hand over the data. So these companies routinely collect huge amounts of data and then the government can just sort of poke through it.’

Soghoian’s most notable work to date, which continues, has come at a benefit and cost to data collecting giants Google and Facebook. Two years ago, he and 37 other computer scientists sent a letter to Google asking the company to begin to automatically encrypt email service so users’ information couldn’t be so easily hacked. Within six months, Google followed through on the advice.

“I’ve been pressuring Microsoft and Facebook and both now offer an option (to encrypt messages), but it’s not turned on by default,’ Soghoian says. “I challenge you to see if you can find the option within five minutes. The problem is, because you haven’t enabled, that if you check your Facebook at Starbucks anyone can hack into your account.

“It shows they’re not really putting their users first,’ he adds, “and my tool of choice is the baseball bat of shame.’

Review: Zeni in San Jose

Review: Zeni in San Jose  Hellyer Velodrome

Hellyer Velodrome