A RECENT 30th-anniversary concert given by San Jose’s modern-dance gem the Margaret Wingrove Dance Company drew from decades of Wingrove’s award-winning choreography. Interestingly, the program showcased not so much an evolution as a range. Wingrove’s work, like the human psyche, like the relationships that inform it, is a study in contrasts: soft and hard, for example.

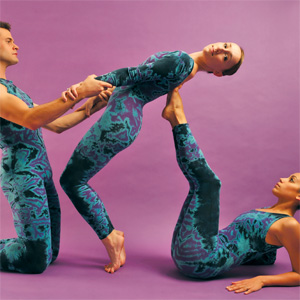

Premiered at the end of the show, Wingrove’s latest piece, Transcend, presents the soft, rounded movements of five dancers so gentle and fluid as they amble, walk in circles and show affection that the women in shimmery dresses appear to be part of a water ballet. Transcend was counterbalanced at the beginning of the production with Dark Edges (1990), where three taut bodies in jungle piebald leotards move combatively to percussive bells and occasionally stabbing violins. The program also included the Paradise Dance Hall (2008) number from The Glass Menagerie, seductive as a tango, with the thrown-back shoulders of the couple (Shannon Bynum and Travis Walker), and yet plaintive as its wailing Cirque de Soleil guitar. In Shatterings (1989), inspired by the untimely death of Wingrove’s son, brief, angry shoves surprise us from amid the slow sadness, the leaning support and the son’s leg tremors or listing shoulder (Travis Walker).

Fittingly, two of the company’s longtime dancers brought amazing solo performances to the program. Lori Seymour, reprising 1999’s Tulips based on a poem by Sylvia Plath, oozed down a banister at the San Jose Stage Theatre in her white hospital garb to a hospital-white set. In the poem, the winter whiteness is disturbed by heart-red tulips, which Plath, narrated by Judith Miller, calls “sinkers around my neck.” Seymour’s aberrant gestures (like arm-rocking a baby too quickly) capture Plath’s sardonic tone; her outstretched positioning echoes the vulnerability of openness evoked by the open-slit Johnny and the words. Howerton pours his elegant style into Lenguaje de Incendios, in moves that seem shaped around the natural curves of his line. Howerton meets the floor as if the shivering glissandos of the music were a sleeve he slides into. In the lines of Octavio Paz, the inspiration for this dance, there is “a silent man up against a wall,” perhaps an impending firing squad (“freedom is calling me to death”), and Howerton dances both the freedom, in dreamy, crescent-bodied swirls, and the death, with an arm clutched to his middle.

The 30th-anniversary program has been committed to DVD with clarity and unobtrusive camera, and even short dances, like the insectlike delight, Snare Game (1987), draw you to multiple viewings. Many dance aficionados will say that good dance, recorded, loses its ephemeral immediacy, but this DVD confirms that what might be lost in these areas is gained in depth.

Review: Puro Peru

Review: Puro Peru  Sebastian Maniscalco

Sebastian Maniscalco