Belle Yang’s ‘Forget Sorrow’ (W.W. Norton; $23.95) exemplifies the graphic novel’s strengths as a strategy for telling family history. The local author and illustrator, who once studied at UC–Santa Cruz, has published books for both adults and children; this is her first graphic novel.

The opening pages seem to have the same trouble as Marjane Satrapi’s 2000 Persepolis; to put it bluntly, that it is the work of someone who is a writer first and an artist second. Yang’s father, whom she calls “Baba,” says that his daughter has a pen in one hand and a paintbrush in the other. In stiffer, more hurried moments among her otherwise expressive drawings—in using a caricature version of Munch’s The Scream—to express sorrow—it seems sometimes as if the paintbrush is in Yang’s left hand.

Secondly, as in Satrapi, Yang appears at first to be burying her more interesting material. The story begins with Belle in flight from a homicidal stalker at her family home; the predator is drawn like a Chinese demon, or as an immense hell-baby grabbing her home. He’s nicknamed “Rotten Egg” by her entire family, after he went to jail for shooting up the office of the lawyer who protected Yang.

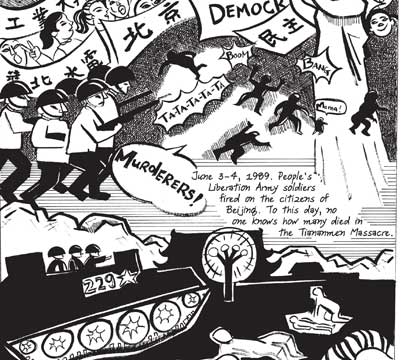

Was this story too painful, too legally dangerous? Ultimately, this tale is an aside compared to Yang’s family saga: how her grandparents endured 20th century China. This is the background for backbiting and rivalries, for the pressures of commerce on a patriarch who longed to receive Buddhist enlightenment.

As prophesied by a Taoist monk, the Yang family is upset by family discord—a petty version of the court intrigues within the palace of an emperor. Ultimately, the Cultural Revolution destroys the Yangs’ holdings.

After some 10 pages into Forget Sorrow, you realize you’re in the hands of a serious storyteller. Yang uses the graphic-novel format for its full potential—to add layers on layers, and also to do what comic art does best: universalize the particular by stripping away everything to an outline.

Some critics might compare Yang to Art Spiegelman, since she’s getting her family history from a father who doesn’t mind blaming her for her failures in life. Yang’s own writing has less detachment and urban crust than Spiegelman’s Maus. There’s more fragrance to this family’s past.

Yang’s strength as a writer shines in her capturing of idiom and folk belief: social pressure makes a person’s eyes turn blue, for instance, or killing a baby swallow will make you go blind.

The tragedy and feeling are out in the open, as is her inability to graft severed roots on herself. A long trip to China exposes Belle to ancient relatives either too formal or too senile to recognize her: “The first Chinese who left for American wanted their bones returned to China, but I was scared I’d die in China, my bones never returned to America.”

Yang’s memoir deserves space next to the best graphic-novel personal histories. Justin Green’s 1972 Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary—reprinted last year by McSweeney’s—was the breakthrough graphic novel about a Catholic childhood in the Chicago suburbs of 1950s, complicated by a serious OCD. The sexual freedom essential to the underground comics of the time makes this a hard read for more modest readers today. (Even Green called the book “A sin of youth”.)

At the time of a 1995 reprint, cartoonist Robert Crumb called Green “The FIRST, absolutely the FIRST EVER cartoonist to draw highly personal autobiographical comics.” This obsessive opening-up led to the literally hundreds of autobiographies and family histories in comic book form, starting with Crumb and his wife Aline Kominsky’s own adoption of the form.

When Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home was named by Time as the best book of the year 2006—not just the best graphic novel, but the best book, period—it was another step out of the niche market for these special kind of non fictions. Bechdel used her experience as a weekly cartoonist, and her life-long love of reading, to make this memoir of her father’s suicide both literary as well as achingly personal. It was a masterwork, an opus that took some seven years to complete, and clearly one of the key works of biography of the last ten years.

Yang’s work continues Bechdel’s pioneering, showing what’s possible with the medium whose potential continues to grow.

Yang was given the birthname Xuan, “Forget Sorrow,” yet she does the opposite: she retrieves her family’s pain in hopes of bringing peace to her ancestors and herself.

A Rare Korean Treat in Santa Clara

A Rare Korean Treat in Santa Clara