Mayor Chuck Reed says he wasn’t kidding when he proposed shuttering 90-plus medical marijuana collectives in San Jose, allowing only 10 to continue to operate, by auctioning licenses on eBay. Confronted with the likelihood that his plan would invite dozens of lawsuits that could last years and cost the city millions of dollars, the mayor responds: Bring it on.

“This is California, everyone litigates,” says Reed, who was a lawyer by trade before moving into public service. “We’ll do what we think is right. And if people want to litigate, that’s their right. I’m not going to back off because I think somebody is going to get upset and sue us.”

But several operators of San Jose collectives say the city will be acting against its own interest in selling medi-pot permits to the highest bidders.

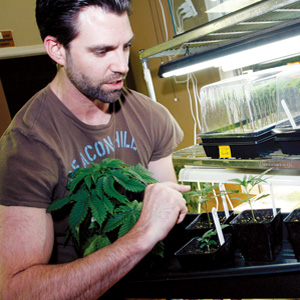

Doug Chloupek, who runs MedMar Healing Center, says that the mayor’s plan will invite participation from the very for-profit dealers it says it wants to eliminate.

“The only people who will have a quarter-million dollars to put up for bid are the out-of-state capitalists that are operating for profit illegally, and they’re not the ones the city wants,” Chloupek says. “It’s ridiculous. Statements like that are why it’s blatantly apparent that the city doesn’t understand the issue.”

Reed says there is no estimate on how much money the city would make through an auction. The idea is to raise as much money as possible to help tackle the city’s perpetual deficit—estimated at a conservative $105 million for the coming fiscal year. The proposal to cap the number of collectives within the city at 10 was put forward earlier this month by Councilmembers Pete Constant and Sam Liccardo and Vice Mayor Madison Nguyen.

Chloupek has been pushing for the city to take a more nuanced approach, which would systematically eliminate undesirable collectives and limit or avoid lawsuits.

By requiring timely tax payments and background checks for past felony convictions, the city would cut out a significant chunk of the troublemakers, Chloupek says. The number of clubs would be further reduced if the city passed an ordinance, which has languished since 1997, mandating that collectives to be located in specific zoning areas and away from schools, churches and parks.

Councilmember Pierluigi Oliverio was the first public official to tackle the issue of medical marijuana regulation in 2009, but inaction on the city’s part allowed the number of collectives to explode. According to city memos, there were 102 medical marijuana collectives and personal delivery services in San Jose at the end of last year, compared to roughly a dozen a two years earlier.

“I think 10 would have been the right number if the council had acted earlier,” Oliverio says. “It’s going to be hard to make it smaller. But to continue at the number it is now is probably not practical.

“I think the council is now fixated on a number, regardless of how they get to it. They just want a number.”

Complicating the matter is a fundamental difference in the way the various city officials view collectives. While Oliverio believes the Compassionate use Act of 1996 and last year’s 79 percent voter approval of Measure U indicates that medical marijuana has a legal place in San Jose, Reed bluntly disagrees.

“You have to realize that all the existing operators are illegal within city law,” Reed says. “They have no rights.”

Drug War 2.0

Dave Hodges started the first storefront medical marijuana cooperative in the city, the San Jose Cannabis Buyers Collective, in July 2009. He says poor legal interpretation on the city’s part has made progress in installing regulation so difficult, even after voters signed off on the taxation of medical marijuana with the passage of Measure U.

“The one big difference is that they’re saying over and over—that you’re illegal for even existing—is what got us here,” Hodges says. “What has happened is the mayor and city attorney have focused all their energy on getting rid of collectives, instead of focusing on how to make sure the collectives are operating efficiently.”

City Attorney Richard Doyle says the city is being forced to deal with a problem it did not create. “I call this the Wild West,” Doyle says, “because there isn’t a lot of guidance from the federal government or the state of California.”

At any rate, Doyle does not seem too thrilled about the eBay proposal.

“I don’t know if we recommend the auctions from a staff level,” Doyle says. “That was the mayor’s idea.”

Hodges, who has been involved in legal battles with the city, says the city’s policies criminalize collectives—in direct conflict with the Compassionate Use Act.

“It’s not legal to cap a city of a million people to 10 dispensaries,” Hodges says. “Prop. 215 very specifically was designed to make it easier to access cannabis.”

Even if the eBay-style system is put in place, it will likely take somewhere between six and 18 months for the city to rid itself of collectives not given a stamp of approval.

“It takes a while to get everything in place,” says Reed, who laments the state’s refusal to give better direction to cities and counties.

In a perfect world, Reed says, medical marijuana would be sold “at CVS and Walgreens, just like hundreds of other substances that are controlled and are potentially a problem.”

The city council has no plans to discuss the matter until April 12, and no committees will be studying the matter before then, setting up a silent yet dramatic timetable for the future of medical marijuana in San Jose.

“If they do an auction or a lottery or any kind of pool, you can take it straight to the bank—they can expect millions and millions of dollars spent in litigation from the clubs,” Chloupek says. “It is absolutely the worst-case scenario the city could consider.”

20 Percent of Bridges Have Structural Deficiencies

20 Percent of Bridges Have Structural Deficiencies  Livefeed: SJ Eats

Livefeed: SJ Eats