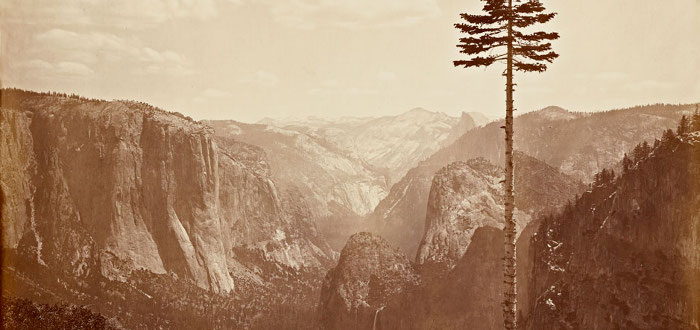

For sheer difficulty, 19th-century photographer Carleton Watkins deserves to be called heroic. Hauling his equipment up primitive paths in Yosemite in the 1860s, Watkins would rise before dawn to coat his glass plate negatives with noxious chemicals in a small tent before making long exposures—weather and wind patterns permitting. That the results were not just picturesque but often majestic seems somehow miraculous in the age of digital cameras.

A new show at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center offers a rare chance to see some of Watkins’ best views of Yosemite, the Pacific coast and Oregon. The images confirm his reputation as not just the finest American landscape photographer of the 19th century, but also as the equal of his best-known follower in the high country, Ansel Adams.

Born in New York, Watkins (1829–1916) came to San Francisco in the early years of the Gold Rush. After a stint at clerking, he learned the burgeoning craft of photography, venturing south to work with James May Ford in San Jose.

In 1861, Watkins went big with a supersized camera designed to produce 18-by-22-inch negatives, so-called mammoth plates, and headed for the newly opened Yosemite Valley. In an era before enlargements, photographs were produced one-to-one size by contact printing. The bigger the negatives, the bigger the final images. Watkins recognized that the natural wonder of Yosemite deserved the scope of the mammoth plate.

The images on display come from three luxury albums of about 50 mammoth pictures apiece, representing works from the early 1860s to the mid-1870s. The images have been individually mounted for conservation purposes.

The term black-and-white doesn’t really do justice to the subtle range of gray tones. Watkins was adept at massing large area of dark and light but also excelled in capturing shadings between the extremes. It’s not hard to take a conventionally beautiful picture in Yosemite, but Watkins found perspectives that transported the merely wondrous into the realm of the miraculous.

Standing back from the photos emphasizes the spectacle of Yosemite, its grandeur and scope, enhanced by the extreme depth of focus that Watkins achieved with his long lenses. It is also possible to lean in and be entranced by crystal-sharp details of twigs, leaves and blades of meadow grass.

Watkins turned two peculiarities of the era’s technology to his advantage. His skies are generally light-beige swaths—his film wasn’t sensitive enough to record the masses of clouds that become familiar in later Yosemite iconography. Watkins cannily used this phenomenon to create solid rectangles to balance the rocks and rivers below. Due to long exposure times, rushing falls and crashing surf turn pure white in the prints; thus Watkins could capture the movement rather than the static instant of the water. The effect is one of tumult amid calm.

Several times, Watkins goes the opposite direction and uses the still waters of lakes to conjure magical reflections of North Dome and El Capitan. The mirrored images appear perfect at first, but a closer examination shows how the tiniest movement of the water softens what it doubles.

Watkins often uses trees as framing and punctuating devices. The dark pines on the left and right extremes of The Yosemite Falls, 2634 ft., Yosemite (1865–66) establish an inner frame leading to the white cascade in the deep distance. Sometimes, fallen tree trunks in the foreground echo the thrust of granite formations in the far beyond.

Less painterly is the jumble of dark and light, thick and skinny, tree trunks in the foreground of Multnomah Falls, Cascades, Columbia River (1867)—even the falls are split in two and displaced horizontally by the tangle of midground foliage. The expansive orderliness of Yosemite is supplanted by an almost junglelike confusion of vegetation.

His 1867 image of the sprawling settlement of Portland is marked by a bare ruined tree stump in the center foreground. It intrudes like a warning beacon of what civilization can do to the wilderness.

This admonitory trunk raises the question of just how Watkins viewed progress. His photos add to our image bank of Yosemite as a bastion of pristine beauty, but the tourists were already there by the time Watkins arrived.

Watkins’ photos of the Malakoff Diggings in Nevada County evince considerable ambiguity; he creates stately patterns of water nozzles against a cliff collapsing under the pressure of hydraulic mining. Modern interpreters (including Robert Dawson in one of the essays in the show’s catalogue) can’t help but read an early environmental consciousness into such images, but Watkins left little behind in the way of explication about his intentions.

One of Watkins’ greatest photos—Cape Horn, Near Celilo (1867)—depicts a lonely vista of empty railroad tracks receding past a nearly black cliff on the right and a low horizontal ridge on the left with a single telephone pole (an artificial tree, really) at the vanishing point. It looks like a portrait in despair to our eyes—cold comfort wilderness. But maybe Watkins welcomed the arrival of settlers or was just taken by the arrangement of forms. For whatever reason, his photos along the Columbia River and the Oregon Coast are bleaker, more austere than his Yosemite views.

One of the real surprises of the show is Sugar Loaf Islands and Seal Rocks, Farallons (1868–69). A massive rock formation juts out from the sea, filling the frame with only some blank sky and a bit of encircling surf to provide any geographical context. The craggy pyramid dominates until a closer inspection reveals fat, twisting slug shapes—the seals that cling to the rock’s base.

It easily eclipses Seal Rock, an oil-on-canvas by Albert Bierstadt from a few years later. In the painter’s vision, the seals are larger, the skies more dramatic, the pounding waves more tempestuous. The painting seems locked in the past, while Watkins’ image is timeless, both geologically and artistically.

Ramen Gets Whimsical at Kansui in Willow Glen

Ramen Gets Whimsical at Kansui in Willow Glen  Hermitage Brewing Company to Tap Limited Barrel-Aged Beers

Hermitage Brewing Company to Tap Limited Barrel-Aged Beers